|

IT'S one of the most recognised marks in the English language. The Ampersand that jumble of words “and per se &” that was once the alphabet’s 27th letter.

Loved by many a designer and wordsmith for its arabesque style, the ampersand has effortlessly spanned lexicons of words and ideas. With a social fluency that predates social media, you could say that it was one of the first modern social networkers, a matchmaker par excellence. For Grant Harrington, such poetry is not lost. Explaining why he named his butter after this most poetic of punctuation marks, he says: “Butter sits perfectly with an ampersand - just think about it - bread & butter. For me, the importance of the ampersand is that it highlights the importance of staple ingredients needing to be at their upmost deliciousness.” Since launching his handcrafted cultured butter in late 2014, Grant’s commitment to the importance of ingredients has been obvious to anyone (of which there are many) who have tasted his butter. In fact, this attention to deliciousness has governed Harrington’s career from his time as a chef including a stint at Fäviken (Sweden) to his dedicated following at London’s Druid Street Market.

1 Comment

Beyond the world of celebrity chefs, TV shows and cookery books, our chefs have an important role to play in supporting local producers. This was the key message from yesterday’s Terra Madre session, When chefs side with farmers.

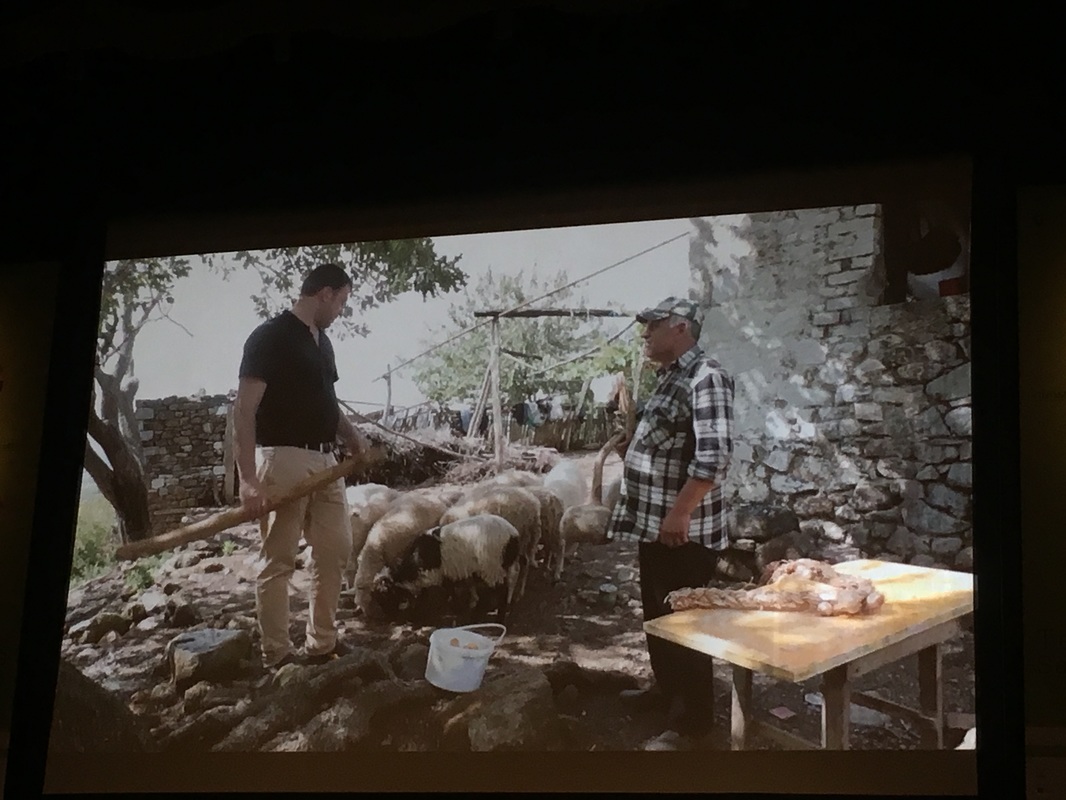

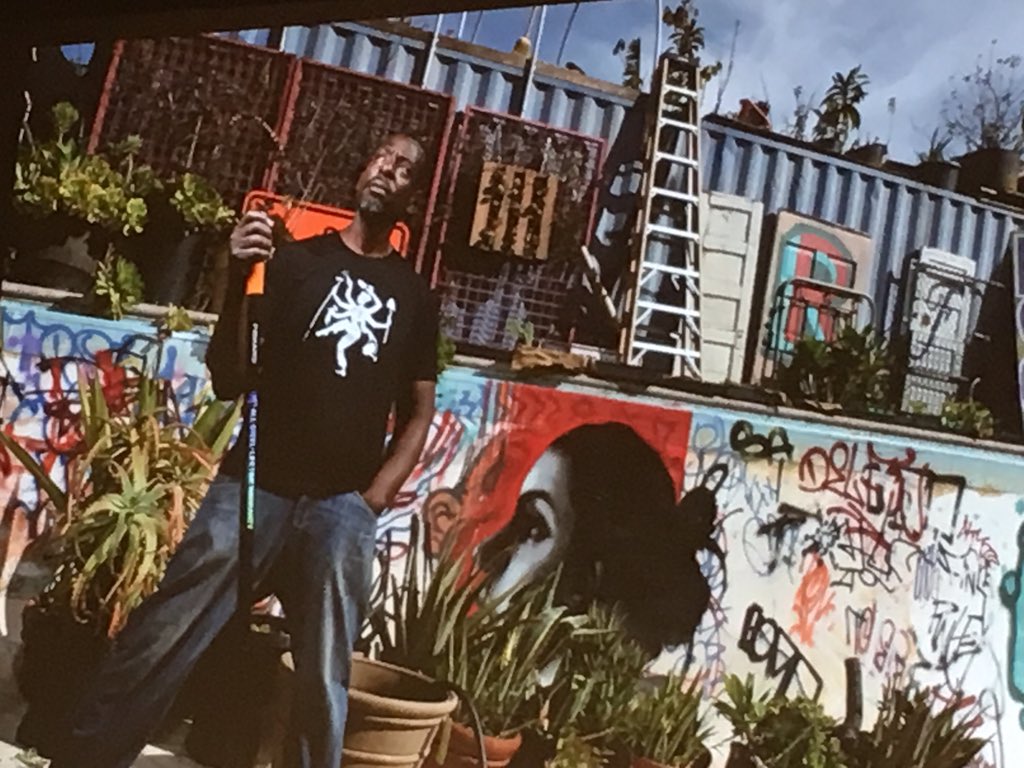

Facilitated by Dan Saladino from the BBC’s The Food Programme, the need for chefs to championfood diversity and support their local producers and farmers was discussed by Michael Bras, Olivier Roellinger, Altin Pregna, and Cristina Bowerman. In this lively and empassionated dialogue about the role of the chef, all shared their optimistic belief in the chefs of the future, the joy and pleasure that comes from exploring and creating food based on local traditions, and of their own passion for championing the foods of where they live. For Cristina Bowerman of Glass Hostaria, the opportunity to support local producers has never been greater. “Our societies are based on cooking, so part of our responsibility is to protect our future”, she said. Working in a city such as Rome where the closest supplier is forty minutes away, she shared her belief that it is the responsibility of chefs to protect agricultural biodiversity. Speaking to the value she places on mentoring and supporting the farmers that supply her restaurant, she called upon all chefs to adopt a craftsman. "Every restaurant then takes care of the survival of the farmer and artisan. What is important is the chef's awareness of this person who invested their life for their passion." Her words closely echoed those of Olivier Roellinger who warned chefs away from the easy temptation of going with the one supplier. Talking about his life as a chef in Saint-Malo Brittany, he likened his role as a chef to one of a story-teller. “I am trying to tell the story (through food) of the men and women who have forged this area”. His fellow countryman, Michel Bras shared a similar philosophy. “Cooking should start with the producer,” he said. Reflecting the theme of the session that true gastronomy is a celebration of one’s surroundings, he described his role as one of “enhancing the image of my land” through a way of cooking that was in harmony with nature. The role of the chef to preserve agricultural biodiversity was described by Altin Pregna in terms of our personal and collective histories. His restaurant Mrizi i Zanave has revived many of the cultural and culinary traditions repressed under Communist Albania. Describing himself more as a farmer than a chef, he spoke of a deep affinity between himself and the 300 local farmers, shepherds and foragers that he works with.“The more cooks that use local produce, the more they increase their value”, he said. The role of chefs to engage in dialogues of eco-sustainability and support local sustainable produce was shared by all presenters. For all, any less was a compromise of their creativity and responsibility. Bowerman said it best when she stated: “It is no longer a matter of choice. We must champion ideas of the intimate relationship between producers and consumers.”Yet all admitted that the adoption of such principles was not without its challenges. As Olivier Roellinger said, “behind every regional cuisine, local cuisine, there is a wonderful diversity. You have to learn cooking again”. This is the challenge and joy when chefs collaborate with farmers. The Slow Food Chef’s Alliance is a network of chefs defending food biodiversity across the world. More than 400 chefs, from restaurants, bistros and street kitchens – in Albania, Italy, the Netherlands, Mexico and Morocco – who support small producers, the custodians of biodiversity, everyday by using products from Presidia projects and the Ark of Taste, as well as local fruits, vegetables and cheeses, in their kitchens. You can discover more about the alliance here. "Why am l leaving my neighbourhood to get healthy food?" Ron Finley on the start of his garden in South Central, LA. @TerraMadre

"Agriculture is one of the primary causes of climate change and, at the same time, one of its most helpless victims. Yet the power to find solutions lies within these communities." This was the subject of today’s Let’s not eat up our planet at the Terra Madre Forum.

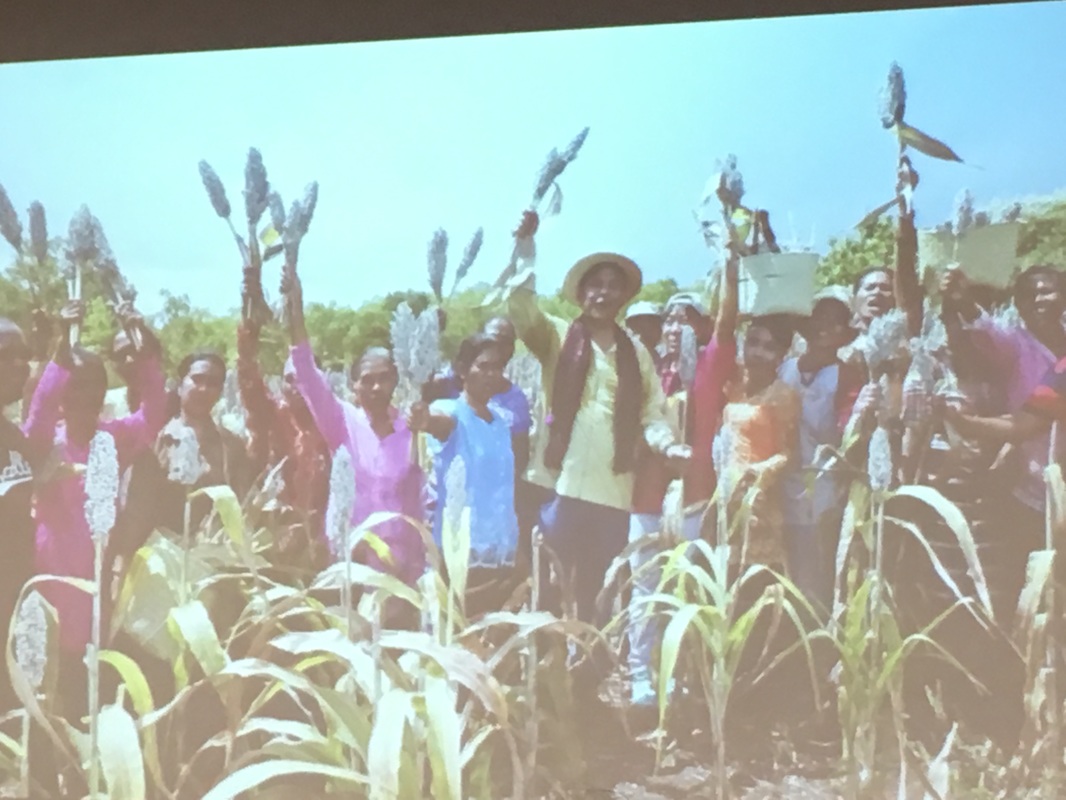

Looking at the consequence of climate change on farmers, speakers presented their experiences of working in and with local communities, of the need for greater global community and how to achieve the balance between global responsibility and local action. So what is the role of farmers in addressing climate change? In Timor through the KEHAIT (The Indonesia Biodiversity Foundation) project, local farmers are returning to the traditional food crop of sorghum after decades of failed rice, corn, and soya bean crops. With only four months of rain a year, the project has worked with local farmers, advocating “local wisdom and local crop empowerment”. Since starting five year ago, the project has grown from four participating farms to a harvest covering 120 hectares. And yet, with the majority of farming being done by smallholders, change needs to be incentivised. According to the Paris-based Good Food Foundation for too many farmers, the issue of climate change is too remote, when eating is about today and tomorrow. When the value of what is produced is not reflected in the market, there are insufficient reasons to engage in these issues. Giving an example of their own fieldwork, the foundation seeks to reduce green house gases while also improving the quality of life of the people that it works with. So working in India, they have funded bio-fuel projects that produce fuel from cow mature. The waste from which is then used as fertiliser and importantly the carbon credits accrued can then by sold. So what is the role of the global community? For the Italian Coalition of Climate Change and Vice President of Slow Food Italy, it is only through a global campaign that action can be forced. For example, despite the promises of the Italian government, there has been a decided lack of action on the Green Act. For the UN Special Envoy for Indigenous People, the question of global community is about global food security. With climate change directly impacting on food availability, she shared her experience of advocating for indigenous people in the charged debates around reducing omissions and drivers of de-forestation. Speaking directly to one of themes of the forum that agriculture despite being such a key industry remains marginal in the political landscape, she reminded us that the subject of climate change is also one of human rights. In Brazil, indigenous people continue to be evicted from their land in the name of agric-business in Brazil. Tucked away in London's Columbia Road is The Brick Kitchen: a pop-up restaurant dedicated to the very best of British produce. A twelve-month sourcing project, the menu features different producers and wine-makers each week, showcasing the wealth of ingredients cultivated in the UK. Each event is an experience of natural cookery, set in a bare-brick kitchen, in the cultural heart of East London. All five courses are based on seasonal ingredient, each one ethically sourced and inspired by independent growers, farms and distilleries. Featured produces include Wild Beef, E5 Bakehouse, Hook & Son, Forager, British Quinoa Company, New Hall Vineyards and Urban Wine Company. This culinary meeting of real bread, rare breeds, sustainable fish and wild forage is a heartfelt homage to British cuisine. You can book to attend one of the weekend lunches here.

For your address book British Quinoa Company, @BritishQuinoa E5 Bakehouse, Arch 395, Mentmore Terrace, E8 3PH t. @e5bakehouse Forager, @ForagerLtd Hook & Son, @hookandson New Hall Vineyards, Chelmsford Rd, Chelmsford CM3 6PN The Urban Wine Company, t. @Urbanwineuk Wild Beef, @Wild_Beef |

ARCHIVES

February 2017

|